Final Fantasy was released in 1987, and over three decades later, it has proven to be anything but final. As the series continues, fans have experienced different eras of the Final Fantasy franchise through sequels, prequels, spinoffs, films, and re-releases.

While this is fantastic for keeping the franchise’s history alive, it doesn’t necessarily give us an incentive to understand this history.

Why is Understanding the History of a Franchise Important?

From a design aspect, it allows us to reflect on previous decisions and understand the progression of features and mechanics, storytelling, and culture. As a fan, it can help us better understand these fictional worlds by immersing ourselves within their worldbuilding, recognizing easter eggs, and fostering deeper connections with others.

This article separates the core numbered games in the Final Fantasy series into three periods based on what I find to be major focal points in those games. While each era is not wholly unique, and most of these games share many similar qualities, the different eras are intended to show how the series’s development has evolved and stayed the same. While I will be talking about features and mechanics, I won’t delve into gameplay to a great degree.

[Warning! This article may contain spoilers]

Building a Foundation – An Era of Fantasy

These games set the expectations we have today for the series and RPGs as a genre. Final Fantasy continued to grow by building on previous entries’ accomplishments, which is where those roots started.

To me, this first era was about delivering a fantasy tale that was unlike any other, and each game was made to best accomplish this.

Final Fantasy

Simple and to the point. This is a classic adventure about saving the world. If sitting around a table for hours and using equal parts imagination, mathematics, and dumb luck wasn’t your ideal adventure, Final Fantasy gave you everything you needed.

If you have played any JRPG, you can probably find something recognizable in one of its earliest forms here.

Final Fantasy 2

With names, backstories, and a combat system that improved your heroes based on the actions the player took rather than gained experience, this second entry set the standard for the series: innovation, change, and a colorful cast of characters.

If the first Final Fantasy was a simple adventure, this was a tale you were intended to connect with on a personal level.

Final Fantasy 3

With the job system, Final Fantasy 3 made it possible for players to experiment with character development. This allowed for a vast number of party configurations, and thus a unique experience beyond random monster encounters.

The story revolves around a theme of balance, which is fitting as this game found a happy medium between the first two in regard to its main cast.

Final Fantasy 4

The ATB gauge was introduced in Final Fantasy 4, and some strategic elements were used in later games.

This was the first entry in the series to center around a central protagonist, Cecil, with a supporting cast of 11 playable characters. Prioritizing a cinematic experience and foretelling an eventual switch to real-time combat, this entry could be called a defining moment in what the series would set out to do moving forward.

Redemption and trauma are the main themes here, while the story also comments on the tragedies of war.

Final Fantasy 5

With a return to the job system that offered even more customization with multiclassing, Final Fantasy 5 managed to keep character development at the forefront of its story.

This was a natural evolution from the previous entry, giving us a polished experience of everything the series had to offer. This entry also straddles the line between both eras with its main antagonist, Exdeath.

Antagonist Master Class – An Era of Philosophy

While remaining innovative with combat and experimenting with new concepts, these games took the journey beyond the mundane “Good vs. Evil” by giving us unique and memorable antagonists.

These Final Fantasy entries also do a phenomenal job of incorporating their respective systems into their separate worlds. If the previous era was about saving the world, this one is all about understanding the world you were aiming to protect.

Final Fantasy 6

With a move to a more extensive ensemble cast of protagonists, Final Fantasy 6’s story focuses heavily on the villain Kefka. In a tale steeped in dualities such as life and death, familial duty, and magic vs. technology, Kefka refuses to accept anything but his desires, becoming the antithesis of the personal journey of each party member.

Neither manipulated by nor a divine force, Kefka is pure evil for the simple fact that they are awful and selfish, even succeeding in attaining their goals. Balance is an important theme here and is prevalent in how character development has little to do with class.

Final Fantasy 7

With loss, environmentalism, and morality as central themes, it’s easy to see why this cast is so relatable. The main antagonist, Sephiroth, is driven mad when he learns of the circumstances surrounding his birth and searches for a purpose, believing a false truth. Likewise, many of the characters wish to protect something due to the loss they have experienced.

The death of Aerith is likely one of the greatest moments of loss in gaming history and only further cement Sephiroth’s position as a calamity within the world. The “Materia System” also brought some interesting aspects to how equipment and skills were used while being an intelligent use of worldbuilding by reinforcing the environmental points of the story throughout the entire game.

Final Fantasy 8

Ultimecia makes for a gripping villain; as she attempts to escape her destiny, she subsequently forces that destiny upon Squall and herself. While some of her dialogue implies she could be a sympathetic villain, the story leaves a lot unanswered, which I find to work in its favor. After all, when it comes to time travel, simplicity is critical.

Squall’s transformation from a loner to a leader to legendary SeeD further showcases fate as a theme. Militarism and the aftermath of war are also major story elements that help define the world by adding context to its condition and the views of its characters.

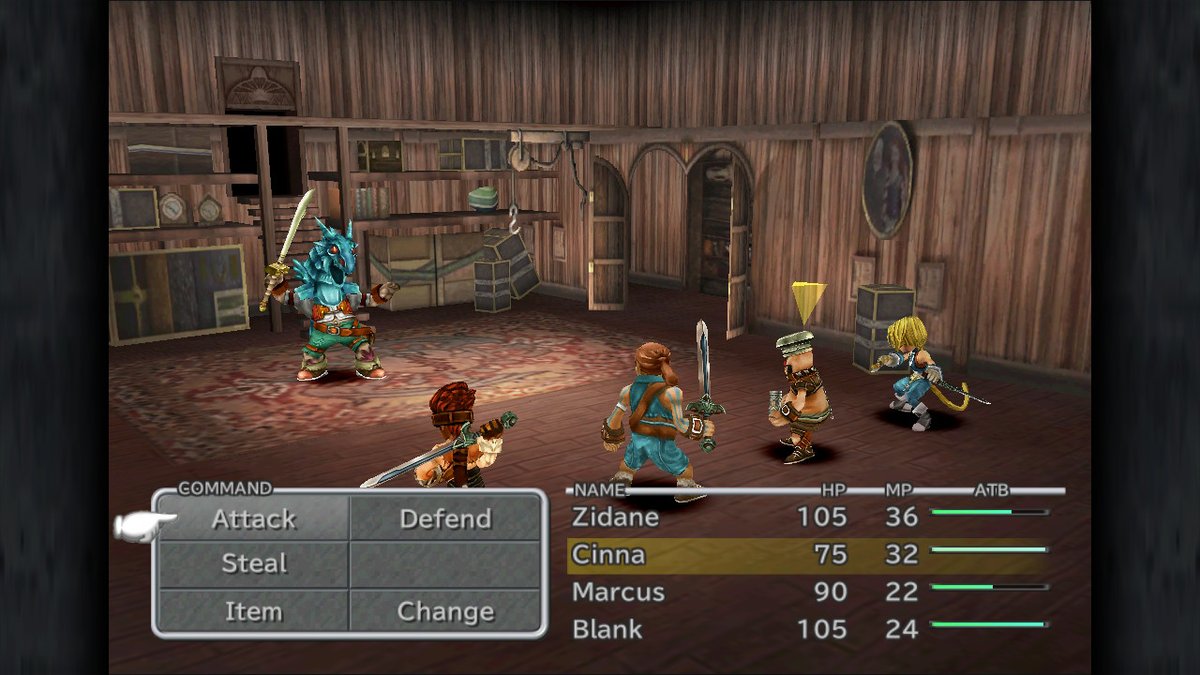

Final Fantasy 9

Life, death, and purpose are the themes found in this entry, and they are utilized masterfully. Garland’s selfish drive to fulfill his goal of reviving Terra robs Kuja of the ability to appreciate his life, eventually driving him mad with grief when faced with his own mortality.

Zidane’s abandonment as a child, Vivi’s identity crisis as a Black Mage, and the fate of the Summoner tribe are just a few of the events that highlight Kuja’s emotional struggle with cruelty. This entry straddles the line between its era and the next, weaving an entire world through its cast.

Immersive Worldbuilding – An Era of Experience

The only era with a sub-category due to design choices. All entries in this section share the feature of highlighting the experience of being a part of their respective worlds. By comparison, these games introduce the player to a world far different from our own, with strange customs and cultures explained by the unique traits of the planet and its society.

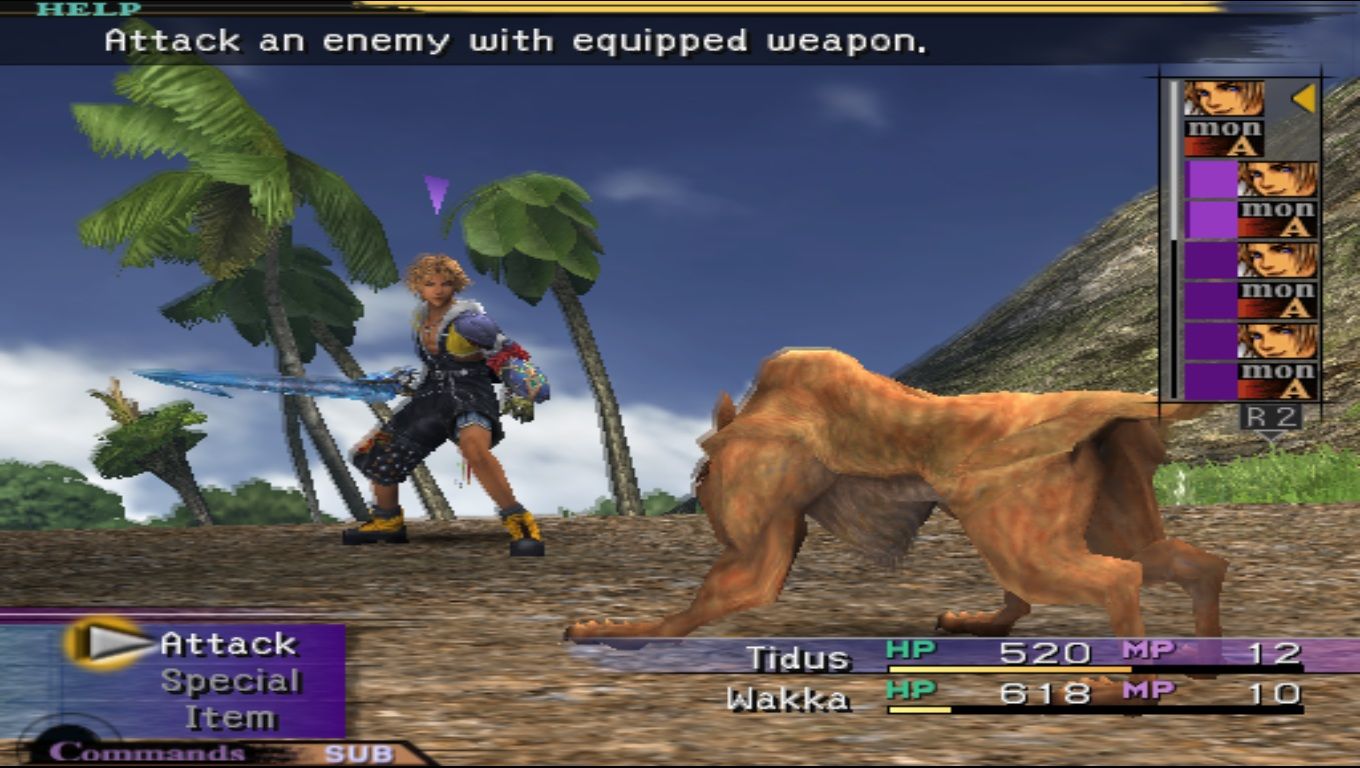

Final Fantasy 10

Spira is a world dominated by religion, a theme portrayed in the many aspects of its story. The deep connection the world has to its tangible afterlife, the Farplane, allows this entry to handle the concepts of death, faith, and sacrifice uniquely while paying homage to FF7, with which it shares a direct connection.

Prejudice and the aftermath of war are also present in the story, echoing back to FF8. These factors give us a group of villains that are very much products of the events in their world. Seymore and Yunalesca are both zealots who use the Yu Yevon religion to reach their goals, showing how easy it is to lose faith. Ironically, Sin starts out as practically a force of nature but comes to represent the sins of the world as a whole as the cycle of sacrifice perpetuates.

Final Fantasy XI & XIV

As an MMO experience, players can work together in a more active playstyle. This switch-up in genre allows for a looser storyline, connecting players to a central plot while giving them vast amounts of freedom. This sense of unity helps players communicate and create bonds in what is typically a single-player experience.

Comradery is a theme driving these experiences, and it lends itself well to explorative worldbuilding. By nature, an MMO style allows players to experience the world in a non-linear mundane fashion, as though they were just another resident of these fantastic worlds.

Final Fantasy 12

The world of Ivalice has a rich history, and it was found in several FF spinoff series before making its debut into the main series. Additionally, players are introduced to the Active Dimension Battle (ADB) system, making combat encounters feel more natural. ADB removes the need for a combat screen, creating an ecosystem of monsters that interact with the player interestingly.

Hunts are one of the best examples of this system, making sidequests feel like a meaningful part of the journey. Weather also plays a factor in combat effectiveness, adding to the validity of the world. With themes of freedom and loss, we get to experience Ivalice through the hardships and personal journeys of the cast, growing our investment in them as the story unfolds.

Final Fantasy 13

Cocoon is a scientifically advanced satellite that rests far above the depopulated and primal world of Gran Pulse. War and ruin eventually lead to the belief that Gran Pulse is a living hell, fostering fear in the people of Cocoon and making them easier to control. In this way, free will becomes a significant theme in the story as the main characters fight against the fate that has been reluctantly placed upon them.

We learn much about these two worlds through the questions we are forced to ask as the story unfolds, though it becomes easy to see the cycle of war has progressed, leaving its mark. Incapable of sustaining itself without natural resources, Cocoon would resort to inciting war with the world below.

This led to the hatred of Gran Pulse, which taught its people to fulfill the selfish desires of the fal’Cie, powerful beings that control humans by branding them with a directive goal. Once branded, a human becomes a l’Cie and risks losing their humanity and sense of self if they do not accomplish their assigned goal or Focus. For our heroes, this means fighting a destiny that would see one of them bring about the genocide of humanity.

Final Fantasy 15

Final Fantasy 15 had players begin its story under the guise of a simple road trip. The young prince Noctis exploring the countryside was a stroke of genius, making the initial journey resonate naturally with those who could relate to any of the sidequests. Players could hunt, cook, scavenge, fish, fly, and devote hours of their playtime in pursuit of mastery in just one of these features.

As someone with fond childhood memories of traveling Historic Route 66 here in the U.S., this was something that I could deeply relate to. With Gladio, Ignis, and Prompto as supporting cast, I found myself focusing on the journey of Final Fantasy more than the destinations. Boss fights could be challenging, beautiful, and fun, but it was the random observations, snappy retorts, and bad jokes that I was eager for. This was not the first entry I found disappointments in, but out of those few, it was the only one that I thoroughly enjoyed.

Final Fantasy 16

Final Fantasy 16 immerses players in an all-new adventure. The tale follows Clive Rosfield, who undergoes personal and emotional trials throughout three different stages of his life. Clive starts as a protective Shield for his younger brother Joshua, who is heir to the throne. As his story progresses, Clive’s life takes dramatic turns, navigating through personal challenges and worldly events.

A major part of the narrative unfolds against the backdrop of a struggle for power. The setting is a dark fantasy world where political intrigues and battles for control over the mighty Mothercrystals are a constant. This world faces the dire threat of the Blight, a destructive force that has the potential to devastate everything in its path. Amidst this, Clive and his allies must find their place, negotiate alliances, and confront enemies to save their world.

Adding another layer to the plot, Final Fantasy 16 introduces the concept of Bearers and Dominants. Bearers, individuals born with magic, are marginalized and exploited in society. Dominants, on the other hand, control powerful summons known as Eikons. They are revered, feared, or controlled depending on their place of residence. Final Fantasy 16 captivates players with its intense battles and grand cinematic scenes, all part of the classic Final Fantasy experience.

It’s still too early to tell if FF16 will take us into a new era for the series or focus on polishing what has worked in recent entries. Nevertheless, we can be confident it will be an epic journey of self-discovery for the characters, players, and series alike.