Ghosting Ghost in the Shell

Ghost In The Shell is a landmark film for anime. It was one of the many great anime films that began introducing anime into the Western mainstream media and revolutionised the image anime had garnered for itself outside of Japan. Based on the 1989 manga of the same name by Masamune Shirow, Ghost In The Shell has blossomed into a franchise that now has multiple movies and series as well as its own Netflix Original. So it baffles me that I’d not seen it up until literally today.

I’m a huge fan of anime, whether it be the incredibly talented Satoshi Kon and Studio Ghibli films, to series such as Hunter x Hunter or Full Metal Alchemist. The thing is that Ghost In The Shell was both too confusing to get into, and not intriguing enough to bother trying. Its multiple films and series, all with their overly complicated names such as Ghost in the Shell Arise: Border 1 – Ghost Pain and Ghost in the Shell SAC_2045, led me to believe that it was an impenetrable franchise that, like the Neon Genisis Evangelion series, was best left untouched.

Contentious Casting

When the remake came out in 2017, that mindset changed for me. Here was, by all accounts, a retelling or remake of the original film that would encapsulate its themes, narrative beats, and characters into a concise, two-hour flick that I could enjoy and then use as a pretence for having not seen the original. Of course, that film was marred with its own controversy, namely the whitewashing of some of its characters. The casting of Scarlett Johansson, who by that point had reached the peak of her career and showed no signs of going down, was certainly a controversial choice, but an entirely understandable one. This is a complex, philosophical anime movie filled with anime tropes, gore, over-sexualisation of its central female character, a distinct lack of any real action, and is a franchise that was not entirely in the peripherals of Western audiences.

While the original film did help bring anime to the attention of the West, it was quickly overshadowed by easier to understand, and more approachable anime movies. It didn’t help that its follow-ups followed far more distinctive anime tropes, and left those who were unaffiliated with the franchise or with anime completely in the lurch. Bringing a remake of an already forgotten film about the meaning of life and death to an audience who are indoctrinated with superhero flicks was going to be a mountainous task. Therefore, casting an actress who was already in the public interest, an actress who was familiar with working on high-budget films, and playing empowered female action-heroes made a lot of sense. The casting would then go on to be defended by the 1995 film’s director Mamoru Oshii, who said he believes the outrage against the casting to be politically motivated, and “believe[s] [that] artistic expression must be free from politics.”

Regardless of the outrage, the remake went on to do poorly, both critically and financially. People couldn’t get over the fact that it paled in comparison to the original. However, as someone who hadn’t seen the original, I found myself genuinely enthralled by the film, and now regard it as one of my top ten films of all time. No, seriously. But over the years I’ve felt as if I should really give its predecessor a try, to see if I am still fervent in my belief that the remake is better, or if the original truly is the superior version as everyone says.

The Point Of This Article

So, I have watched both movies, back to back and will review both of them independently of each other. I will not compare the movies in their respective reviews, but will instead judge each of them on their own individual merits. Once the reviews are finished, I will compare both films, discuss what they do better and worse over one another, and then come to an entirely opinionated conclusion on which of the two is better.

Ghost In The Shell (1995) Review

During my time studying film, I learned an important lesson in storytelling. To successfully engage an audience and create a compelling narrative, the audience must, in some way, be able to relate to or understand the overarching ideas, themes, and motifs. The problem with Ghost In The Shell lies not entirely with its laboriously slow pace, its incomprehensible narrative, or the fact that it lacks action, but with the fact that it is so unfeeling and so monochromatic, that it both succeeds in its attempt to portray a world without life, and in making me completely unsympathetic in its plight to do so.

“Ghost In The Shell predominantly deals in long, barely animated sequences of characters discussing philosophies and abstract ideas in ways that convolute an already confusing narrative.”

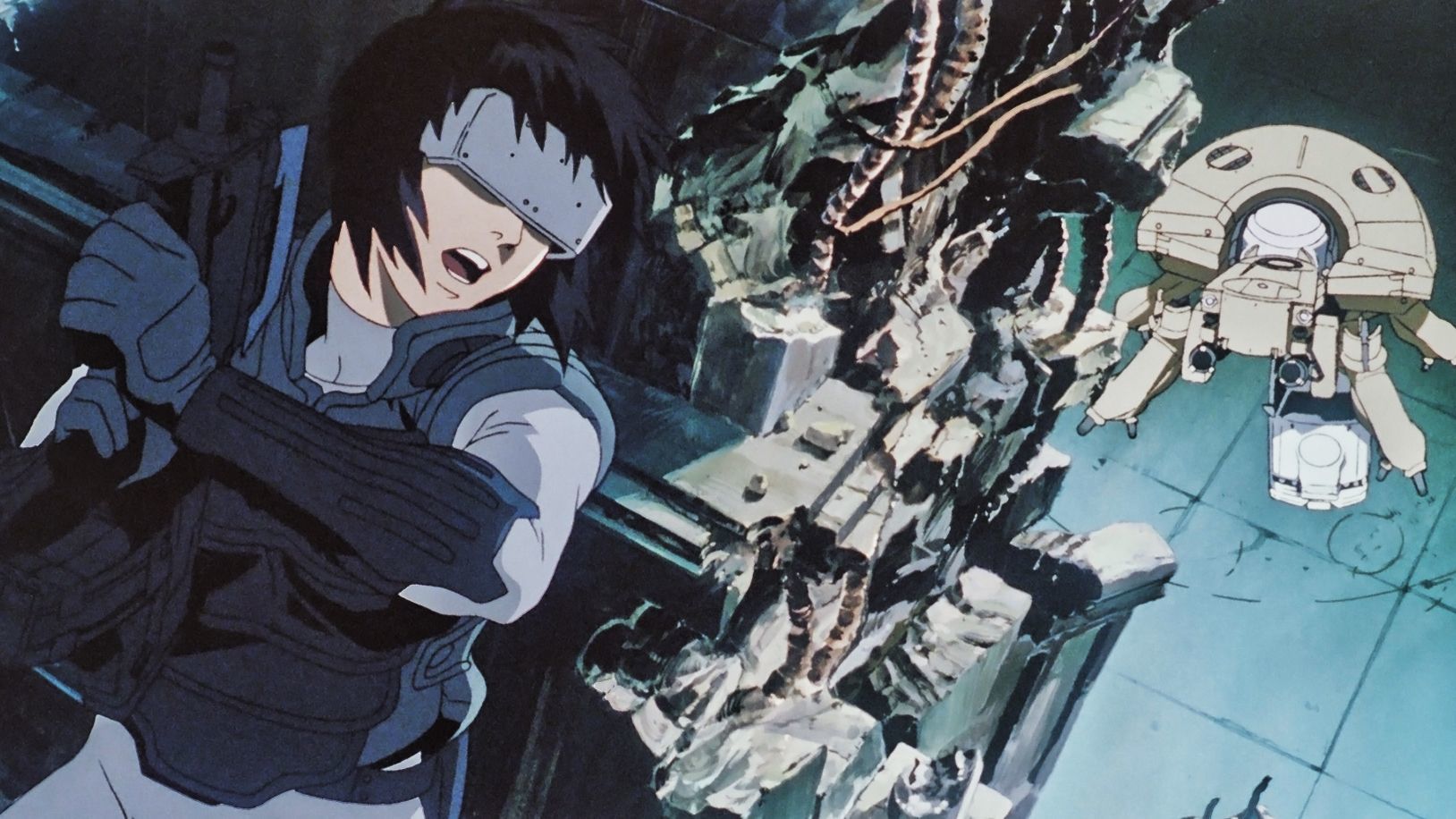

Ghost In The Shell is about a world inhabited by both cyborgs and humans. A special sect of cyborgs, simply named Section 9, have no qualms with completing covert operations by any means, as is demonstrated by the opening scene of the film. Throughout the course of the film, Section 9 is chasing after a dangerous cyber-hacker who goes by the name The Puppet Master.

They’re named this after their ability to dive into another person’s cybernetic consciousness’, give them false memories, and manipulate them into doing their bidding. In an earlier sequence in the movie, we see a prime example of The Puppet Master’s manipulation, as a garbage disposal worker goes around the city hacking into various devices believing that he is spying on his ex-wife who doesn’t exist. Aside from this, however, The Puppet Master is more of a narrative-mechanism to portray the film’s ulterior motive: a philosophical discussion about life, death, and reality.

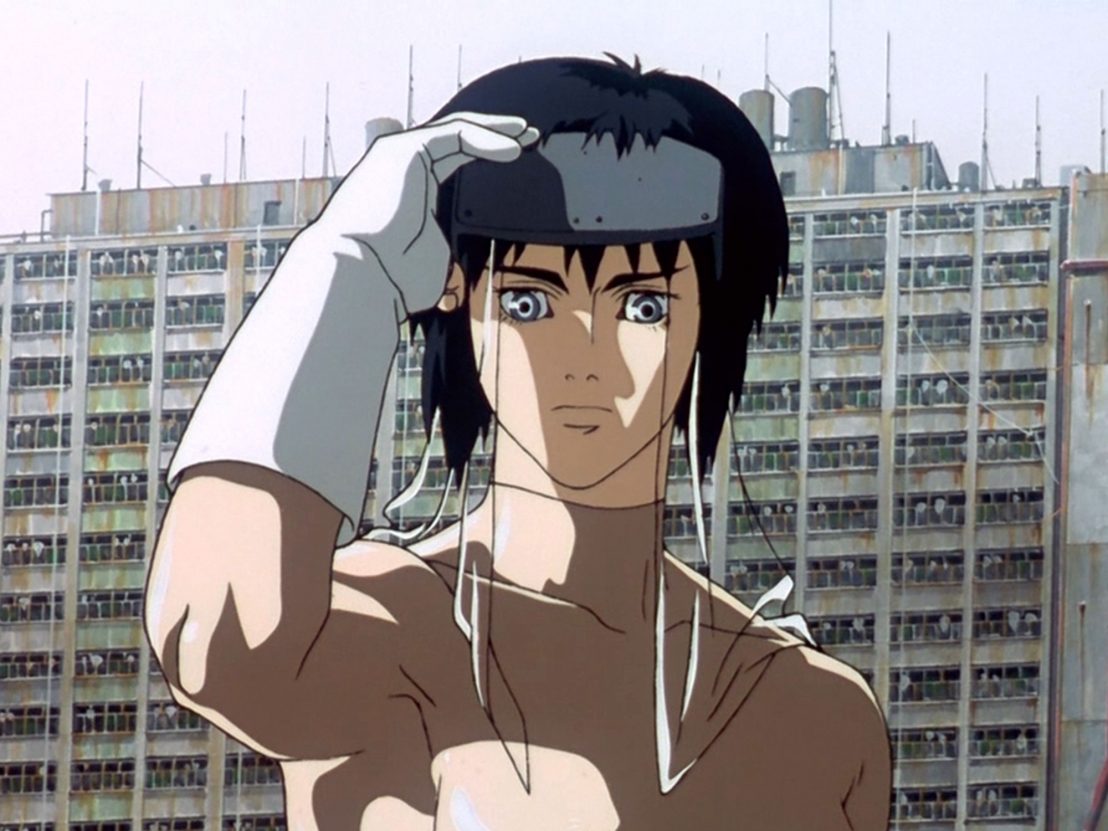

In reality, the film is about Maj. Motoko Kusanagi, our female protagonist. She is a member of Section 9 and is predominantly cyborg, and feels a deep sense of disconnect from the rest of the world. Her internal struggle is the central focus of the film, and is ultimately the films most interesting aspect. During a sombre five-minute sequence we see her as she wanders the streets of an ill-defined cyberpunk world, surrounded by mannequins, advertisements, and faceless passersby. It’s a striking sequence, both visually and emotionally, as it reflects the inhuman nature of Ghost In The Shell’s world, as well as the central characters’ internal struggle for self-worth and connection.

Masquerading as an action film, Ghost In The Shell predominantly deals in long, barely animated sequences of characters discussing philosophies and abstract ideas in ways that convolute an already confusing narrative. Their discussions lead to thought-provoking ideas that feel more pertinent for 1995 than for 2021, but they still hold a significant amount of relevancy for today’s overly indulgent internet-age. For example, their discussion on memories and reality, unwittingly foreshadows the rise of false-personalities and lies that plague social media. It shows a world of people who lead second lives, enhance themselves in entirely unnecessary ways (who needs eye enhancements that make your vision worse than just having regular eyes?), and show this to others with a sense of unearned pride.

“Its narrative is overly complex and confusing and requires an intricate knowledge of a world that is hardly explained nor illustrated to the audience.”

The issue with Ghost In The Shell is that it is entirely unfeeling. Its narrative focuses on the political inner-workings of a world that’s not clearly defined to the audience and is about cold and calculating forces that act entirely on selfish and malicious grounds. The characters mope around for its breezy one hour and 20 minutes run time, philosophising about how they can’t die and therefore cannot experience life, how they can’t reproduce, how they can’t enjoy something as basic as swimming, or how nothing is truly theirs and their whole life is a lie built on cybernetic parts and falsified memories. While all of this is ultimately interesting, it feels hopeless, cold and heartless, and is therefore impossible to engage with on any level.

As I’ve mentioned, its narrative is overly complex and confusing and requires an intricate knowledge of a world that is hardly explained nor illustrated to the audience. We get a brief explanation of the conflict between the various Sections, but beyond that, it’s impossible to discern what the difference between each Section is, or what the importance of The Puppet Master truly is. The film concludes with the revelation that Section 6 created The Puppet Master for espionage and to allow them to deport a character who is briefly mentioned towards the beginning and never elaborated on. Ironically, for all the talking and exposition that goes on throughout the film, there’s very little substance to help the audience get to grips with what is actually happening.

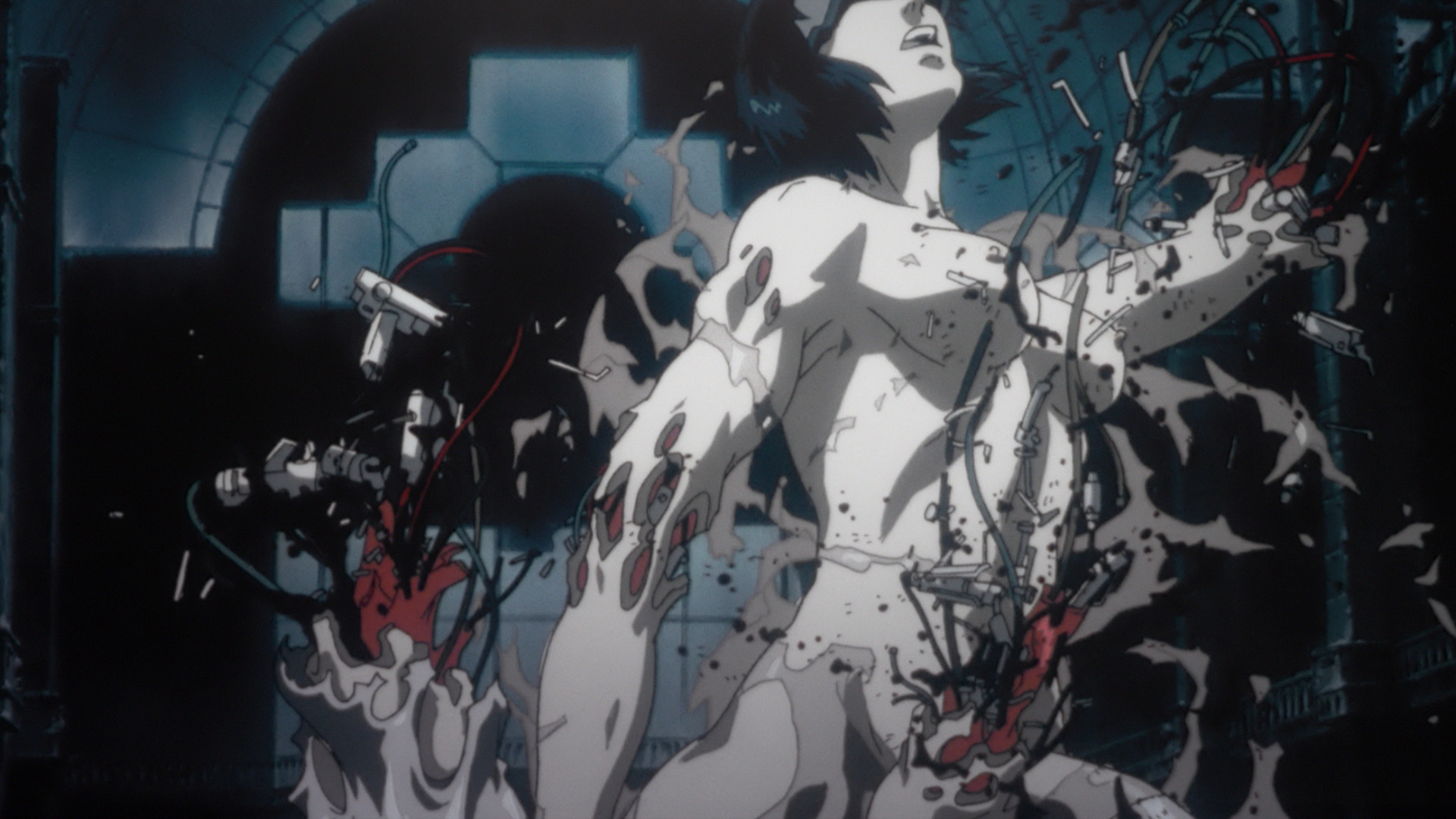

Initially, when the film did come to its inevitable conclusion, it felt as if I watched the first two episodes of a show, and was finally getting into it. Upon reflection, I believe the ending to be the only moment of emotion the film is willing to display, as Major Kusanagi is transferred into the body of a young woman, and has merged with The Puppet Master, something he proposes to her as the next step in their evolution.

The emotion lies in the fact that she finally has some form of connection to a side of her reality. Alas, it is not with her humanity. It’s ultimately very monochromatic in its finale, a saddening realisation that the central character lacks any real humanity, and is willing to give it all up to embrace a psychotic self-aware programme to evolve her cybernetic side. It adds to the overall bleak outlook the film ultimately carries, which, for me, was unfortunate.

Conclusion

It’s not that I dislike Ghost In The Shell, in fact, far from it. I enjoy its themes, it’s slower and more introspective pacing, and there are some genuinely impressive visuals. I respect its unfettered attitude towards its morbid portrayal of life and even enjoy its highly stylised action sequences used to keep the viewer awake. But I don’t think the film can rely on the strength of its philosophical babble alone to ensure its success.

Ultimately its narrative is more interested in its philosophical discussions of life, death, and the meaninglessness of memories that it fails to deliver an engaging or even focused narrative. Just like watching The Turin Horse, a two and a half hour movie about a peasant couple slowly starving to death, is only fascinating for its bleak outlook on life, Ghost In The Shell is an intriguing watch if only to indulge in boilerplate philosophical ideas. Unfortunately, as a film, it ultimately fails to engross or entertain.

Ghost In The Shell (2017) Review

In an age filled with unbridled potential, we resign ourselves to the confines of a medium that both enhances connection and reduces it to a blinking line on a screen. The internet age has liberated us and allowed ourselves to evolve beyond the confines of the human body, enabled us to explore our own minds, genders, and sexuality. It has also created a dependency on lies, on warping the truth so that we may appear more than we truly are.

In the internet age, we have simultaneously abandoned our humanity and regained it. We have exchanged personality for limitless knowledge, and yet freed ourselves from the confines of predetermined characteristics and biological traits. We can be whoever we want to be both physically and emotionally, but in migrating to a medium where we become ever more insignificant, we continue to instil the antiquated norms that to be human is to be completely and utterly prosaic.

“It is Mira’s internal struggle to understand what it is to be human that kept me enthralled.”

Ghost In The Shell 2017 toys with the idea of what it means to be human and transposes it to a future in which people have very much altered themselves beyond recognition. It imagines a world in which the human form is entirely meaningless, that one must alter oneself in order to be their best self. Its world is engulfed in a wave of self-obsession, of a narcissistic desire for self-evolution, self-worth, and meaning. It supposes that the next step of human evolution is to rid ourselves of our human forms entirely, to not only enhance ourselves with cybernetic parts but to simply place our minds into a shell and live freely through it. In doing so, however, one relies entirely on memories, on the thoughts and feelings of the past, something that can be entirely altered.

Our central protagonist is Major Mira Killian, a woman who is informed that she is the very first person to have their mind and consciousness extracted and put inside of a shell. She works for Section 9, a subset of the Department of Defence who uses cybernetic enhancements to complete covert operations, who, throughout the course of the film, are hunting down a cyberterrorist named Kuze. It is not the central plotline that is the focus of the film, however. Instead, it is Mira’s internal struggle to understand what it is to be human that kept me enthralled.

Mira feels a complete disconnect from reality, something visually represented by glitches in which she sees memories of her past self leak into the real world, and struggles to maintain that she is anything more than a hollow shell with the ghost of her past self desperately clinging on for survival. Throughout the course of the movie we see her offer consent for doctors to help fix her, an act that feels distinctly human. It shows that she is different from the robots being dissected and experimented on. Instead, she is displaying the most human trait of all: free will.

“It feels like a highly prevalent message for a time where individuality is compromised, and every facet of oneself is entirely fluid.”

Ghost In The Shell 2017 attempts to explore the themes of humanity, identity, and free will but does so by treading over well-trodden ground. While discussing them brings life to the character of Mira and allows for her character depth to mirror that of the overall narrative, it ultimately does so by philosophising about boilerplate ideas, as opposed to delving deeper into the complexities of having a depersonalisation-derealisation disorder. Its attempts at exploring freedom of self, of body, and of mind are interesting, and the fact that the film accepts that our reliance on memories is ultimately futile, and we should act not on memories but on actions, is appreciated. It feels like a highly prevalent message for a time where individuality is compromised, and every facet of oneself is entirely fluid. It’s a positive outlook and leaves the audience hopeful as opposed to continuing to feel oppressed.

Outside of Ghost In The Shell 2017’s philosophical narrative, it is a well-shot, well-choreographed action flick that successfully balances a coherent narrative with action sequences. Everything feels purposeful, both action and philosophical scenes add to the overarching narrative and character development, as opposed to feeling like filler or stop-gaps to break up any potential monotony.

Unfortunately, while Ghost In The Shell 2017 does its best to develop its central protagonist in a meaningful way, it does so to the detriment of its overburdensome cast. There are simply too many characters to keep track of, and as such the development needed to explore the motivations behind the villainous characters is lost. Ironically, their lack of depth makes them feel entirely one-dimensional and lack any form of humanity. They are simply used as instruments in Mira’s character arc, which is ultimately very disappointing.

Conclusion

I really like Ghost In The Shell 2017, more so than this review likely conveys. I think its a well-executed action-film, that successfully balances its thought-provoking discussion on what it means to be human while keeping the viewer entertained with well-shot action sequences. While it certainly could go further in exploring its themes with more subtly and depth, I strongly believe that this is one of the better explorations of identity and freedom of self in the blockbuster sphere. It can’t compete with the more thoughtful films of directors like Michael Haneke and Xavier Dolan, but it does its best while still trying to entertain the masses. It’s not perfect, but it is a riveting film that goes slightly beyond what is expected of Hollywood and delivers a film with a lot to say.

Comparisons

I believe that the success of a Ghost In The Shell film lies in three key components. Firstly, there are the visuals, or at the very least a depiction of a future wrought with self-obsession and misery. Secondly, there is the philosophical element and the degree to which it is explored. Finally, there is narrative and the character development of the film’s central protagonist. In order to best explore each of these key components, I will be separating them into two segments. The first will discuss the narrative and philosophies of each film, and the second each of their visual styles. I will then conclude by deciding which of the two films succeeds in the majority of these components, and crown it the superior film.

Narrative And Philosophy

For the most part, Ghost In The Shell 1995 and Ghost In The Shell 2017 share the same narrative. They both centre around a female protagonist who is disillusioned with reality, and, along with the other members of Section 9, must take down a cyberhacker who is manipulating others to do their bidding. The key differences lie namely in motivation, for both the central character and the hacker.

Villains, Motivation and Suspense

As previously discussed, I believe Ghost In The Shell 1995 to be an utterly confusing mess when it comes to its narrative. It is too wrapped up in its philosophies to fully explore its narrative about political dissonance, espionage, and humanity. For example, its hacker, The Puppet Master, is kept in the shadows and doesn’t materalise until the latter half of the film. Upon doing so, their motivations are laid out for us, but as there had been no prior development towards their character, or even set up that Section 6 were behaving in an unscrupulous manner, it doesn’t come as a shock nor surprise. Because the experiments on The Puppet Master were not disclosed earlier, it makes it difficult to sympathise with their cause or even ideals.

Conversely, Mira’s connection to Kuze is what ultimately drives her to discover more. Her quest to uncover the mystery behind Kuze mirrors that of her own journey for self-discovery. While one could argue that the same should be said of the 1995 version, I’m not wholly convinced. The lack of real connection between Motoko and The Puppet Master makes their bond at the end of the film devoid of any real meaning outside of Motoko’s abandonment of her humanity.

Kuze being introduced as a character earlier on in the film, and even his motivations being established clearly in the second act, allow Mira to make a discovery, and therefore a well-informed choice by the end of the third act. In contrast, Motoko’s choice to abandon her humanity is based not on an understanding of The Puppet Master and their motivations, nor really as a result of having lost faith in the people around her It stems more from her dissatisfaction with herself and her detachment from her humanity. Ultimately, while this is still an interesting discovery, its lack of connection from the central narrative creates a sense of dissonance within the film itself.

Both films share the concept of multiple villains, but where the 1995 version had an ill-defined Puppet Master and a faceless Section 6, the 2017 version had Kuze who was integral to the development of the central character, and Mr. Cutter, who at the very least offered a one-dimensional personality to the shadowy organisation behind the creation of the key villain. As it is ultimately the villains of both of these film’s who drive the central mystery-based narrative, it is then a failure of the 1995’s version to have not clearly defined the motivations and acts of its villain earlier, as to establish a grounds on which its central character makes their key discovery.

By having the discovery of The Puppet Master’s true identity and intentions being made during the third act of the film, you create surprise or shock instead of the suspense. As both of these films are action-mystery films centred around a murderer and hacker and their true identity and intentions, it’s a shame that the 1995 version completely fails to get the key component of a mystery film right.

The Opening Scene

Ghost In The Shell 1995 opens with Motoko leaping off of a building and exploding the head of a nefarious politician who would have gotten away with his unscrupulous actions had she not. While this scene does introduce us to Motoko’s violent side, as well as the immoral nature of Section 9, it does little else to establish narrative or character. The film does attempt to tie in the opening to its central narrative by the third act, but due to its rapid nature, and the fact that it is throwing the audience in medias res, when it is revealed to have a connection, it’s unlikely you’ll understand why.

Ghost In The Shell 2017’s rendition of this scene is used to greater effect. Not only does it flesh out its world by having the Hanka scientist converse with a representative from Africa, and show the differences in how each culture utilises robotics, but it also establishes the abilities of the film’s central villain, Kuze. In the original 1995 version, outside of a few lines of dialogue, The Puppet Master’s abilities aren’t revealed until a later scene in which the garbage disposal man is being manipulated. In the 2017 version, no time is wasted, and it is shown from the get-go that Kuze has the capabilities of manipulating whatever he likes and getting them to do his bidding. This scene also establishes the connection between Kuze and Mira, by having the Geisha bot (with Kuze’s voice) speak directly to her.

In the 1995 version, during the garbage disposal man scene, it is only clear that he is being used by The Puppet Master once he’s taken into custody. While the 2017 version rushes that character’s development, blending him with his contact who Motoko later fights, it does further establish the control Kuze has over his subjects. In contrast, the 1995 version never really establishes how powerful The Puppet Master is, and never really sets them up as being a genuine threat. It isn’t the man under The Puppet Master’s control that attacks Motoko, but his contact who is, all things considered, independent of The Puppet Master.

Ultimately this comes down to a difference in the villain’s motivation, as discussed previously. While The Puppet Master and Kuze are, ostensibly one and the same for narrative purposes, The Puppet Master is less of a villain and more of a vehicle for the film to explore its philosophical ideas. Kuze poses more of a threat because they’re more of a villainous character, at least initially. Having a personal grudge against Hanka, and a connection with Mira makes them a more developed character, and therefore more interesting.

Motoko vs Mira

I’ve spoken a little about the differences between Motoko and Mira, but I want to expand on it a little further. We can glean from a very surface-level analysis of the two characters that Motoko represents a true disconnect from our humanity, whereas Mira represents a more positive and hopeful look at regaining it. From the perspective of their respective times, these two outlooks make perfect sense. In 1995 technology was on the rise, but it didn’t have this all-consuming presence that it does today. Instead, people were fearing the worst. What if it eventually did become all-consuming? Motoko’s abandonment of her humanity and her acceptance of her cybernetic side are proof of this fear. They represent it.

In today’s society, and by extension 2017, we are feeling the divide that technology brings with it. We want to recapture the glory days before technology, or at the very least when it was in its more primitive state. It’s why the 80s and 90s have become trendy again, and why we spend so much time longing for the past and not the future. 2017’s exploration of humanity, and wanting to reclaim it in a world where there is none left, makes perfect sense. It’s the antidote to the misery that social media and our internet age brings with it.

In essence, both of these outlooks are perfectly acceptable and understandable for the time they were made. While I did critique the 1995s version for its bleak outlook on life and humanity, I ultimately don’t think it is an inherent issue with the film itself. It was a product of its time, and as such a harsher, more critical look on technology and the divide it may bring makes sense. But I don’t think that Motoko’s journey to coming to the conclusion she does, to abandon her humanity, makes as much sense in the context of the film as Mira’s journey of self-discovery does.

The lengthy sombre scenes of Motoko wandering around the city may evoke a sense of self-discovery but are perhaps a little too subtle to make her final decision have any real impact. Conversely, Mira’s journey is riddled with exposition and lacks any form of subtly. Where the 1995 version had lengthy, abstract moments of philosophical babbling, the 2017 version replaces it with characters telling Mira why she is as she is, and Mira telling us why she should be different. It’s not that the 2017 version expresses Mira’s insecurities without subtly, its visual storytelling shows us her disconnect from reality. Unfortunately, though, the lack of subtly in the 2017 version and the abstract nature of the 1995 version means that neither film successfully explores the anxieties of not understand one’s own identity.

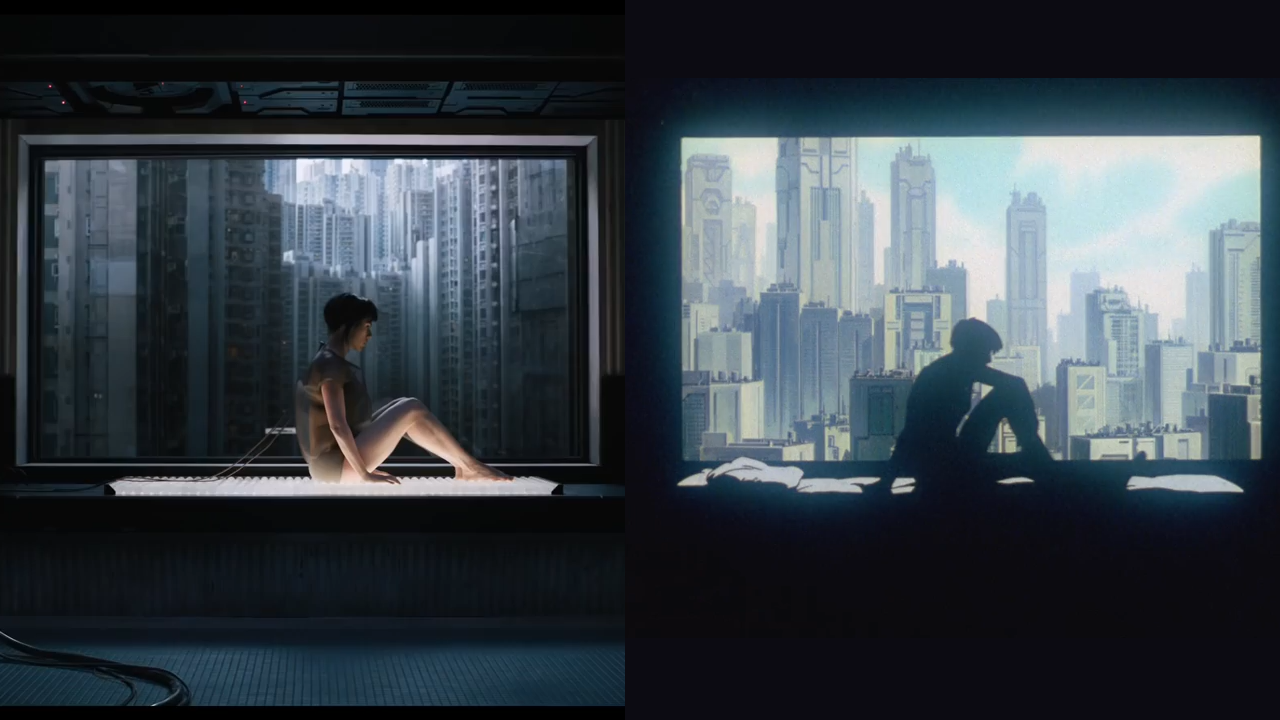

Visuals

It is difficult to compare the visuals of an animated film with that of a live-action one. The animation quality of the 1995 version wasn’t as high as it could have been had the film been produced twenty years later, and so it seems unfair to judge it against a movie with a budget of 110 million dollars. What I will compare, however, is style and world-building.

Style

The 1995 version is unfettered in its use of gore and nudity. Where the 2017 version has Mira wear a flesh-coloured suit whenever she uses camouflage, the 1995 version simply has Motoko exposed. Where the 2017 version uses little to no gore (including a scene where Dr. Ouelet is shot, but there’s no wound or blood), the 1995 version has heads exploding and blood pouring from every possible orifice. You could argue that it’s a sign of the times or a difference in culture, but the question is what makes a better film.

I’d argue that no style is better than the other, ironically. This is predominantly due to, as discussed previously, the difference in time. When the 1995 version was produced, the cybernetic enhancements and alterations to one’s body were seen as excessive, and gluttonous almost. And while the 2017 version doesn’t necessarily portray the alterations in a positive light, it does show that a balance between altering oneself and still retaining one’s soul can be a positive change.

In 1995, being transgender, or non-binary, or bisexual weren’t nearly as accepted or as openly commonplace as they are now. A narrative about the excessiveness of altering one’s body in 1995 makes sense, at least for how social norms worked back then. Even though it’s ultimately wrong by today’s standard, the overuse of gore and nudity to portray a world obsessed with excess and having more makes sense. In 2017, while you could argue that it was all toned down to achieve a PG-13 rating, I firmly believe that its lack of excess when it comes to gore and nudity represents the film’s ideas a little better. Its portrayal of the positives of changing oneself to be more comfortable in one’s body is beautiful. Having the gore and excess of the original film wouldn’t work in conjunction with those themes.

World Building

In regards to world-building, I believe that the 1995 version is far better than the 2017 version. Ghost In The Shell 1995 is far more unique in its vision of a world torn apart by its own desire for self-aggrandising. The 2017 version isn’t less unique because it borrows from that film, but more because it borrows too heavily from the other cyberpunk-themed films before it. While the 2017 version is more distinct in its visuals, and certainly more visually appealing, I think that the 1995 version is better at portraying its ideas and themes in a more visually subtle and engrossing way.

I can’t help but go back to that scene in which Motoko explores the city as sombre music plays in the background. It’s an incredibly moving scene, and in such a short space of time says a lot about her own internal struggles and the world she inhabits. The 2017 version lacks this. It is epic in scale, it manages to recreate a lot of the same visuals from the 1995 version and even expand upon some in certain cases, but it can never encapsulate the hauntingly beautiful nature of the original film.

For all the impressive sets, gorgeous camerawork, incredible CGI, and talented costume design, the 2017 version cannot match the same originality that the original possesses. I implore you to watch that scene if only to fully appreciate why the 1995 version excels at establishing its world in a visual way.

Conclusion

Writing this article has made me appreciate the original more than I thought I would. When I first watched it, I wasn’t impressed, but the more I discuss it, contemplate its themes and how it has gone on to influence a whole new generation of film, the more I like it. Unfortunately, I don’t think it is as good as the remake. The remake is ultimately more focused, more coherent and has clearly benefitted from the years of Ghost In The Shell content that has come after the original. It’s not that I think the original is bad, but comparatively, it suffers from too many narrative inconsistencies and is far too engrossed by its own philosophical discussions that it ultimately fails as a film.

While its successor lacks its subtly and interesting exploration of abstract ideas, as a film I strongly believe it is far superior, if only because it makes more sense than the original ever will. I love both though, and the more times I rewatch the original, the more I’m certain I’ll enjoy it. Unfortunately, the remake was never going to receive the critical acclaim it deserves, because it had a film with such a legacy to compete against. I don’t think that Ghost In The Shell 2017 is a good argument for remaking films. More often than not I am against the concept. But I do believe that in the case of Ghost In The Shell, a remake was necessary in order to fully expand on some of the ideas and characters from the original film.

Ultimately though, this is just my opinion. I am in no way trying to disregard the immense achievements of the original film, nor the incredible fan support it deserves. Clearly, the 1995 Ghost In The Shell is beloved by so many, and for good reason. I just think that the 2017 adaptation deserves a little of that love sent its way.